Tale 12

THE VAULT

“The Cork crowd are looking for some 9mm ammo,” Marsh told Edwards.

“Well, give them some.”

“Yeah. But we have to go to near Mungret to get it.”

“Mungret! Where the fuck is that?”

“Near Limerick. But it's not with the Jesuits....be too obvious that.”

Edwards was puzzled. “What you fucking on about?”

“Whose gaff?”

“It's some big-wig deadman's house. It's a vault in a Church of Ireland graveyard.”

“Jesus! How the fuck did it get there?”

It was some time back. Marsh and three others were coming back from Tarbert in Kerry, in the red Volkswagen with a box of ammunition, when they saw a garda checkpoint on the Dock Road in Limerick. They managed to turn the car around without being noticed and headed back towards Mungret. Marsh decided to go for a piss at an old graveyard. A family vault caught his eye.

“These fuckers must have been hob nobs,” he muttered, as he fumbled around the vault. He pulled at the door, and it swung open.

“For Jaysus sake, leave it alone.”

Marsh was kneeling beside the door, which was about three feet high. He peered into the dark chamber. When his eyes became accustomed to the gloom, he could see that it was about seven feet deep and about eight feet long. The floor was about four feet from the bottom of the iron door. There were two rows of coffins, each containing about four coffins stacked on top of one another. It was difficult to count exactly because of the darkness, and also because the bottom coffins had rotted and been flattened by later generations of dead. He could see one skull quite clearly in one mangled coffin, and some bones extruded from another as if the skeleton had made a vain attempt to escape from the crushing weight of later entries. The scene was one of silent devastation. The men surveyed this nightmarish spectacle with long languid looks.

“So that’s what it all adds up to in the end.”

“No bail for anyone down there.”

Marsh jumped up smartly, dusting the knees of his trousers.

“Find a fucken better dump than that,” he challenged.

Arguing with him was futile. He insisted he had discovered one of the best and safest ready-made dumps in the country. The macabre thought of dead men guarding the ammunition appealed to him.

Marsh, Edwards and Davis had overstayed their time in Hogan’s pub and it was dark when they left for the cemetery near Mungret. When they arrived the moon was peeping intermittingly through scudding clouds. Sometimes the trio waded in pools of moonlight and sometimes they melted into the darkness as they moved about like tipsy ghosts among the crooked crosses and headstones. Marsh took to hiding behind tombstones and jumping out in front of Davis with the torch they had brought switched on and shining on his grinning face from the chin upwards.

“You'd never imagine how dark the country is,” said Davis as he pushed Marsh away and the moon disappeared while drops of rain were sprinkled in the wind.

The men were a little merry from their few drinks. Edwards tripped over a small railing and crashed onto a wreath with a glass cover. In the silence of the graveyard, the noise sounded like a bad car crash. In the distance, a dog barked. The three were saying “shhh” to each other while at the same time bawling with laughter.

Marsh was the first to recover, and he told the other two that they would have to pull themselves together and cut out the prick acting. No sooner had he uttered the words when he tumbled over a grave, and all three were bawling again.

Now Davis, fed up with Marsh’s messing behind tombstones with the torch, had taken control of it and he led the way. Even so, every now and then there was a stumble and a curse followed by a burst of laughter from whoever had fallen.

After half an hour the laughing had stopped. The men got very serious, for the unthinkable had happened: they could not locate the vault. In fact, they did locate a vault which Marsh insisted was “their vault”, but no matter how many times they pawed and groped around it on their knees like blind cripples, they could find no iron door.

After many arguments, they finally agreed that the only thing to do was to return early in the morning and sort out the unexpected puzzle in the cold light of day.

The day had begun drearily when they returned to the graveyard the following morning. They soon discovered that the whole cemetery had been tidied and the iron door on the vault had been bricked up. Edwards cursed every bricklayer in the country. Marsh examined the brickwork. He said that it was definitely not the work of Jason the bricklayer, otherwise, it would have fallen down.

After buying a hammer and a chisel in Limerick, they decided to do a tour of the area. Near Mungret they came across the ruins of Carrig-o-Gunnell. It was high on a hill overlooking the Shannon river. The gauze veil that had obscured the sky earlier had thickened, there was a strong breeze and, as always at the Limerick end of things, the threat of rain to come.

“I've read about this place,” announced Davis, “It was owned by Donal O'Brien.”

“He left it in some fucking state,” Edwards replied otiosely.

“It was blown up by Ginkel during the Williamite wars.”

Marsh surveyed the ruins with a blade of grass in his mouth: his trilby hat pushed back and askew on his head. He stared down the long, steep slopes which fell away on all sides from the crumbling turrets and towers. He began to laugh.

“What's funny?”

Marsh was pointing down the hill and shaking his head from side to side. “Jaysus Christ,” he spluttered out through a mouth full of laughter.

The other two looked at each other, and soon they too had fallen victim to the laughing disease. They had no idea what Marsh was laughing at, but that seemed to make it all the funnier.

“Imagine, just imagine,” Marsh laughed on, “being a brickie’s mate and carrying those fucken boulders (his arm swept around in the direction of the castle ruins and back down the hill) up, up that fucken hill. Jaysus.”

He almost dropped to a sitting position, and he kept shaking his head from side to side as waves of laughter convulsed him.

“Sixteen fucken hours a day, he groaned, “with just a ten-minute break...for...a...piss.”

“Complain to the shop steward,” Edwards gasped, coming into the story. Marsh began waving his arms dismissively.

“Can't, can't...the foreman is after hanging the fucker from that battlement yonder.”

“He got his fucking rise so.”

The laughing trio continued to act out the harrowing aspects of their imaginary 16th century trade unionism. Davis became the foreman, and he sentenced Marsh to be fired from the tallest battlement for whistling while at work;-if people wanted to imitate birds, they would have to have a go at fucking flying. He told Edwards that he did not expect any man, any man at all, to work more than 24 hours in a day. Edwards made gestures of suitably grovelling gratitude. Ructions, in his absence, was rolled into the Shannon in a barrel of rum. The game petered out as they headed down the hill to the red Volkswagen.

After a meal and some pints in Kildimo, they were back in the graveyard again. The sky was like a bar table near closing time, full of black ashy clouds, pooled and dripping. Marsh began to chip away at the brickwork. The whole place echoed with the clink, clink of the chisel.

“They'll think the fucking skeletons are riding.”

Davis watched Marsh remove the last of the brickwork. They pulled open the small iron door. Sure enough, in the light of the dying torch, they could just about make out the ammunition box on the vault floor, wedged between the two rows of coffins.

Marsh entered the vault and his feet crashed through a coffin and then a second. He was up to his waist in coffins and cursing. He leaned over and reached down for the box: it was heavy. To get a better grip he had to extricate himself from the wrecked coffins and squeeze between the two rows. The vault filled with the sound of crackling timber, as if a madman was loose in it. When he bent down to lift the box the row of coffins on one side of him tilted and pressed against him.

“I'll fucken kill yez,” he cursed as he tried to shoulder the coffins back.

“It's just like the last day when yer man comes 'round,” muttered Davis.

After more swearing and what seemed a ferocious row, the box appeared on the vault door ledge. The vault itself was left filled with smashed coffins and broken skeletons of long-dead people, as long forgotten.

These bones which Marsh was disturbing with the casual malice of his trampling disregard were the bones of another nation. Well, maybe never a real nation, just a wannabe nation. The Anglo-Irish one, of which now only bones remain.

And oh! how they were disturbed. By so much more than Marsh and from long before Marsh was so much as a gleam in the saucy eye of his daddy's lecherous libido.

Before these bones were suchlike; back when they had organs and juices and appendages for this and that, and the other; when the all of them was altogether held of a piece by string and skin; even then, even alive, they were disturbed. By an existential angst rooted in the dislocate of idea and identity, and they themselves now dislocated.

First and foremost from the Book of Invasions.

After the flood, before the plague, the sons of Partholon fought the Formorians. Then the bagmen came and settled in Erin. Some say they rule the provinces still, the rivers and the banks of them. High Kings among us yet.

Long-armed, silver-handed, the sons of the daughters of Danu fought and again at Moytura. Then all the miles from Spain came the Gaels to Tara.

Vikings sailed to market and built towns. Thus Brian met Njal's Burners with Brodir at Clontarf and left what was mortal to him there. As all the while Viking begat Norman, and Norman came to Erin.

Turn, turn, turn again.

The Gaels were easy-going, and the Gaeleens even more so. Happy as the days were long, they were lithe and light and laughing. Leastways, Norman found them so. Becoming more Irish than the Irish. Inevitably so. Indubitably so. In bed mostly.

Which is where it comes to it. Comes to it after all the pushing and shoving all the grunting and groaning. Tears, laughter, smiles, grimaces. And when it comes to it, all we all of us want is to be held through the darkness, to make it through the night. Then loosed upon the day, for the want of it.

So far, so much. And by such, by such. As in Sicily and Syria, so in Erin also, Norman blended in.

But turn.

After these floods of Partholans, Formors, Danaans, Milesians, Gaels, and Vikings. Following this flood of Fitz's. A Henrician flood. And shortly after, a shower of Billys.

A book now not so much of invasions. A Book of Conquests now.

Against the Irish and the more Irish than the Irish, the Tudor Gentry came. A nation in arms against a noble rabble, these Sidneys and Spensers surged. First, they cleared the lords of the roses from England’s green and pleasantry. Their new broom then, swept clean of Plantagenets, brushed into Ireland.

Where they conquered as the noble rabble ran. O’Neills, Maguires, O’Donnells, off on their toes to find holiday homes in France and Spain. They found them Winter Quarters.

Whereby, with no Gaelic Princes now to give them orders, their lower orders lowered themselves at last to the ground and snored. Bards ochoned the last of their rightful Kings. Cheered Charlie and booed George. While Paddy slept.

Turn.

The Tudors passed but the Gentry and their Church remained in Ireland. The English nation and its national church in Ireland. And the Henrys did not become more Irish than the Irish, or Irish at all. Their national church in Ireland kept them to deliberately warm beer and calculated slaughter. Nothing of whiskey, nothing whimsical, nothing Irish about them at all.

Bara. Tari. Baratariana.

So, they thought themselves the Anglo core of a new Irish nation, and, in 1782, volunteered themselves for that. Legislating themselves an independence, they declared themselves a Patriot Party. Then stood around waiting for Pat to Riot a long hot summer of their national transformation.

Nothing doing, muttered Pat. Flyman in amber slumber.

Turn again.

Billy then, in Belfast, stood fast upon the square. He mustered on the level. With a trowel in his hand in the gaze of that all-seeing eye. Demanding the Rights of Man and a life for Pat. A life without Kings, the only Captains his own.

Still, half-sleeping Paddy rose to Tuberneering’s day. Still, half-sleeping Paddy fell on Vinegar Hill. Yet, somehow, falling, Paddy stirred. He was half-awake. He’s waking still.

Turn, turn, turn again.

Unheeded, unheard, the bones wailed on. They had nothing better to do, nothing they could do but watch the new revolution controlled by a man whose instincts were conservative and who gave the ‘no rent’ manifesto a reluctant approval and later in 1886 The Plan of Campaign of John Dillon and William O’Brien was a scheme not liked by him but his big triumph was Gladstone’s Act of 1881. The Act reduced rents by 20 per cent and allowed for further reductions so that most of the landlords became convinced that they were going to be abandoned by England and that it would be better if they allowed themselves to be bought out by the State under Land Purchase rather than face the inevitable which came soon after from Davitt and the Land League.

And the bones having whispered when the Fenians rose, lay in trepidation as figures moved in Phoenix Park shadows and Cavendish and Burke lay dead. Not the end of the foreign yoke but the Irish Republican Brotherhood are preparing and planning.

To the wind and the rain outside the vault. And Tommy Marsh inside it, the end product of nearly two hundred years of national development that turned a comatose Gaelic peasantry into a nation of... they moaned....and moaned.....into a nation of foul-mouthed louts and layabouts, the bones cried out, complaining bitterly. A nation of disrespectful scuts of illiterate tinkers' gets, the spittoon-swirl swill, the coarse, ignorant, unwashed leavings of long-nurtured lack of culture.

Wailing amidst bits of sticks and the scattered stones of a celebrated history, some broken bones. Announcing a crime and bemoaning a mystery.

The criminal mystery that was Tommy Marsh. Not so much a question of what he was doing or why he was doing it. More a matter of how the fuck the likes of him were allowed to be at all. At all? Just to be where Henry had once been but was no more. For all that Henry had been so much more than Marsh, so much better than Marsh could imagine. For all that, it was Marsh now trampling Henry underfoot, and worse, not heeding, not caring, not giving it any thought at all.

As Edwards drove their getaway back to the loud and lively, well-fleshed bony life of Dublin, neither he nor Davis spoke. Marsh in the back seat was feeling the weight of the weather. Half-dozing, snatches of past conversations played higgledy-piggledy in the back of his mind. About the strangeness of loose change in tight pockets. The silence of late light from distant stars. The sadness of wrong numbers. The call of the Peacock.

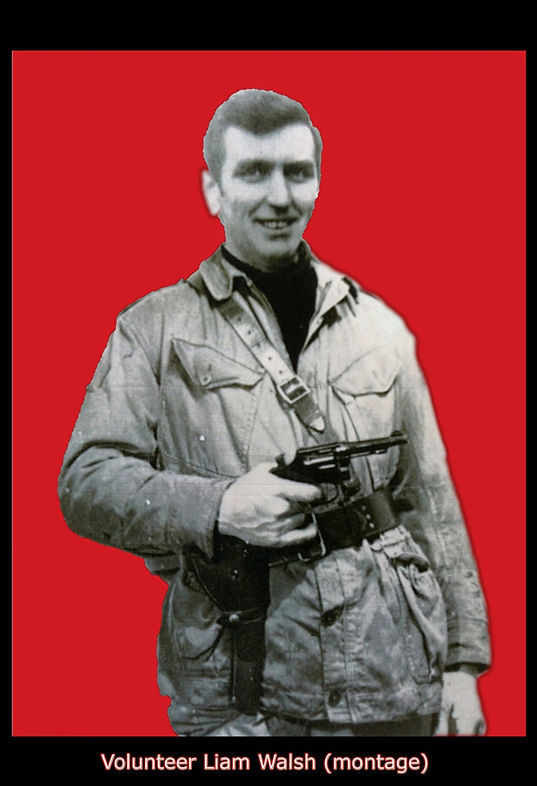

They were soon back in another graveyard. This time in Dublin for the funeral of Liam Walsh. It was shortly after the release of Ructions. He had been released early from Mountjoy for his part in the 1968 Ballyfermot car chase, in which shots were allegedly fired at the gardai. And in which the woman who phoned the gardai and fucked up the operation, whatever it might have been, was still living. Now he found himself as part of the colour party for the Walsh funeral.

Walsh was killed in a premature explosion in Dublin on October 13th, 1970. Martin Casey was injured in the incident but made a complete recovery.

Walsh joined the Republican Movement in 1954 and became Commanding Officer of the South Dublin Unit of the IRA. A welder and fitter by trade, he was interned for a time in the Curragh. At the time of his death, he was on bail, having been charged with taking part in the bank robbery in Baltinglass, County Wicklow in August 1969.

The explosion occurred at a railway line at the rear of McKee Army Base off Blackhorse Avenue in Dublin. The operation was carried out as a publicity stunt to draw attention to the plight of the nationalist minority in the North at that time.

Walsh’s funeral was organized by Liam Sutcliffe and Tommy Weldon. It took place on the following Saturday. According to The Irish Times:-"The funeral took a long route to the cemetery, passing through James’s Street where men and women marched in lines behind the colour party, the hearse and guard of honour of men in green jackets and black berets. After halting outside Dr Steeven’s Hospital, where Casey lay injured and under guard, the cortege moved up the quays to the beat of a muffled drum."

In O'Connell Street there were more than 1,000 marchers. They paused at the General Post Office where a piper played the National Anthem, then closed ranks while two men held revolvers high and fired four shots in sudden and apt salute.

About 3,000 people in lines of three marched from Harold's Cross Bridge to the cemetery. These included members of Official and Provisional Sinn Fein, the Labour Party, men from Citizen’s Defence Committees and Saor Eire.

At the graveside, Geri Lawless went over Liam Walsh's career, from entering the Republican Movement in 1954, through internment in the Curragh, to the Bogside and Belfast in 1970.

Tommy Weldon remembered how he had spent six months guarding itinerants against eviction “the poorest people in the land.”

The funeral ended with Weldon quoting James Clarence Mangan's “The Nameless One” ”'He shed a tear for those in sorrow, from here to hell'.”

In a frenzied Peacock later that day a hoarse Richards asked Ructions: “Are you going to throw your hat into the ring for the Chief of Staff position?”

“Ah no. I expect I'll just remain a general like the rest of 'em.”

THE MARSH VAULT