IRREGULARS

Tale 27

THE BURIAL OF THE SARDINE

“This reminds me of Frank Davis’ landscape painting,” said Casey in a reverential tone as he gazed towards Three Rock mountain.

The other three burst into laughter, the merriment the result of a recent Davis artistic commission.

One of the gardens which Fintan Smith, the horticulturalist, attended to was on Eglington Road. The spacious four-bedroom house was owned by an engineer. In the well-maintained back garden, he had constructed a wooden structure that he called a Pagoda but which to Smith looked more like a large doll's house. It had been built to honour the memory of one of the engineer's daughters who had died at a very young age.

One evening Smith was in the back garden pruning a mature Victoria plum tree when the engineer arrived home early.

“The garden is a credit to you Fintan, a real credit. You were born with green fingers.”

“So my friends say,” Smith laughed sheepishly.

In the course of general chit chat, the engineer told Smith that he planned to commission an artist to do a painting of the back garden with the Pagoda.

“I just might know an artist who could get an attractive likeness for a reasonable fee,” suggested Smith.

A few days, well nights really, later he met Marsh in the Peacock.

“How much would he pay?”

“I'd say he'd manage a ton. I mean he’s not short.”

“Well in that case I know the very man.”

“Who?”

“Frank Davis. Did you ever hear of the pound note he painted when he was only a school nipper?”

“No.”

“I heard it would have fooled the Royal Mint.”

“Jesus!!”

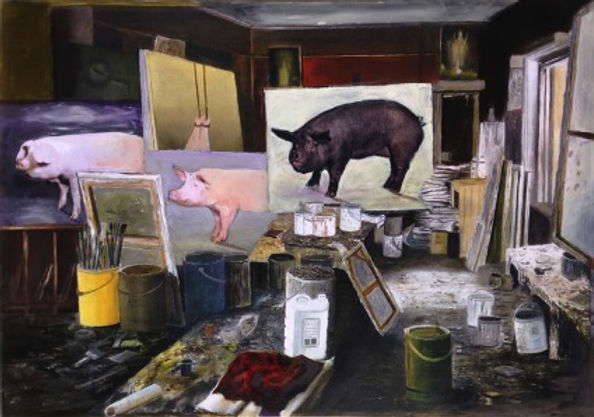

Bates gave a guffaw. “The pound note was painted by O’Donnell. You could say Davis was his understudy. A junior forger really thought years later he tried to present himself as his dealer. It was O’Donnell who taught Davis how to paint pigs, live pigs before O’Donnell moved on to painting dead pigs, rows of them hanging in slaughterhouses.”

“Is he against eating meat?”

“No he loves bacon an’ cabbage. It was then that Davis did the goat.”

“The goat?”

“Yeah the painting with the nanny goat….well it had big horns but he said it was a nanny goat. It was his Yellow Ochre period. Now some of those paintings to me looked as if they were the fucken result of someone getting a bucket of baby shit and throwing it in front of an aeroplane propeller which was revved up to its maximum but,” he shrugged, “that’s fucken genius.”

“Jesus! A fucking nanny goat!”

“Yeah. Fucken standing out in the middle of this field of corn stubble though it looked like a field of baby shit to me. It was conspicuously unaccompanied. This is about isolation. Inness in the environment, he told me. But then he’d say anything once he’d a few on him.”

Smith shook his head knowingly. “Ah, the drink again. Was this for the RHA?”

“No. It was for a competition that Gay Byrne was running on the radio. The goat was looking into the fucken far beyond with his hind quarters facing the viewer and one couldn’t but notice that it had a bunch of dandelions growing out of its arse.”

Smith laughed. “Jesus! Fucking dandelions!”

“If you could have seen it…the dandelion seeds were blowing all over the fields,” he laughed, “of baby shit masquerading as corn stubble. Davis said that the dandelions transformed the familiar, the recognizable into something that is empathy free of maudlin pity. He was saying that by not having the goat stranded in the middle of Lower Gardiner Street with all the attendant shite from the contemporary urban problems of loneliness, depersonalization, crime, pollution and whatever yer auntie Mary is having he was declaring an act of rebellion from the countryside that rural Ireland was fucken alive and kicking and fighting against the cityfuckenphiliacs who were trying to close it down with shite legislation.”

“He has a point there alright.”

The Frank Davis Studio

Later, Davis, armed with his German Praktica camera, accompanied Marsh and Smith to the engineer's house. Davis took a number of photographs of the back garden.

“It's a nice garden all right. As soon as I get them developed I'll get to work.”

“Will it be difficult to work off photographs,” asked Smith with a doubtful look on his face. He was obviously expecting someone to sit in the garden behind a large easel with a beret on his head.

“Ah no. I do little squares and big squares. It's like blowing it up without explosives,” he laughed.

“Sort of like painting by numbers or quadrilaterals,” explained Marsh. Months later he stared at the finished painting and blinked. “Jaysus Frank, yeh forgot to put in the fucken doll's house?”

“I forgot fuck all. I had it in and I had to take it out. It's a fucking monstrosity. It ruined the whole statement that the painting as a work of art makes. It's fucking oeuvre-like."

“I see,” said Marsh doubtfully. He shook his head. “I don't think he'll go for it without the doll's house.”

Davis was emphatic. “There's no way Tommy, I'd sign me name to a painting with that thing in it. Let him fuck off and get some Sunday painter without principles to slap something up so. A Keating or something.”

“Keating!!” exclaimed Marsh. “Wasn’t he the social realist fellow who did the Ardnacrusha paintings? I thought he was the bee's knees of progressiveness?”

“He would have been if he had painted the story, the whole story and nothing but the story.”

“The full story?”

“Yeah, the bodies of the dozens of workers who died and the hundreds who were maimed because of the skimping on safety…”

“Maybe there was no red paint...”

“Or the long strike, or,” continued Davis, “the dilapidated hovels they were forced to live in and the fucking overpriced food that they were forced to buy in the company shops or that the labourers were fucked out after three months because the Blueshirt government was shitting itself that they would organise again. Keating’s paintings glossed over all of that.”

“You’re glossing over our client’s doll’s house. It’s a hundred smackers, Frank,” Marsh pleaded.

“He takes it as it is or he fucks off.”

“OK, Frank. I'll do me best but…”

The engineer ushered Marsh into the well-proportioned dual-aspect living room. Marsh, with much ado, unwrapped the A3-size painting.

“She's still wet,” he announced, putting the painting on a small table against the bay window which looked out onto the road. The engineer squinted into the evening sun. “I can't see it. Put it over on the mantelpiece.”

Marsh placed the painting on the black marble mantelpiece. The engineer's jaw dropped as he stared into the dark green blizzard.

“It's dark and my garden exudes brightness,” he said in a shocked tone.

“It'll brighten up once she dries and once she's hung on a sunny wall,” assured Marsh. “This is the artist's opaque oxide of chromium period. I missed his blue period,” he said regretfully.

“Where's the Pagoda?”

Marsh shook his head and grimaced. “This artist, Mr Davis, is the leading artist of the Drumcondra region. He is a sensitive man, not the kind of person who would cast aspersions on anyone's work but he thought that, in his humble opinion, the painting as a painting did not work as a work of art with the Pagoda in it.”

The engineer threw his hands in the air. “I don't believe this. I'm paying him to paint what I want him to paint and he just...”

“That's his precocious brilliance, I'm afraid. He's impervious to money. You see as his agent I could get him many commissions, yeh know, oulwans with lapdogs,” he gave a few imitation canine pants, “and Siamese cats surrounded by luxurious Turkish cushions but he refuses point blank to paint any animals other than pigs. I've seen some paintings of his pigs and I've said to him...Frank, who wants to be looking at a sow's arse last thing at night and first thing in the morning....there's no money...”

“There's a bay tree there,” said the engineer staring into the painting, “and he has it looking like a dark green Stag's Horn Sumach except there's no such fucking thing.”

“Did you notice all the brush strokes going in the same direction,” asked Marsh, ignoring him, “a sure sign of genius?” Marsh moved back to the centre of the room. He gestured towards the painting, “This is called hallucinatory naturalism.”

“You can say that again.”

“An uneasy marriage between reason and nightmare,” continued Marsh. “It is this ambiguous unease which allows the artist, Mr Davis, to pursue his infantile fears to demand that we, the viewers, emerge from the shadows of our own psychopathologies and embrace the appalling horror of dislocation of our commonplace notions of reality and the timeless place of disturbed melancholia.”

The engineer sat down on the arm of a couch and stared up at Marsh.

“You see Davis not only sexualizes landscape, he rides it, he mounts space-time, he moves through the dissolving terrain of his polymorphic masterpiece like a mad genius, allowing his reclusive personality to merge, like Tarquin, into the shadows of his bizarre, lurid mind. This confuses us. This newly discovered psychoanalysis of nature reminds us of a waking nightmare. He is obviously embarrassed by his eccentric talent...”

“He fucking should be,” the engineer muttered.

“Of that, there can be no doubt. No doubt at all. The threatening elegance of the foreground is lit with a disquieting light that if cut by a surgeon's scalpel would blind the sun. If I was religious I would say that we were looking at a precious gift from a superior being. I ask myself where does this haunting, palpable eloquence unfold from to jolt our senses and alter our mood. It comes from the fragments of nothing. It is nothing. The universe is nothing, fuck all, and nothing is unstable.”

“And you'll get nothing, sweet fuck all off me for it,” the engineer cut in.

“That's a pity,” said Marsh, shaking his head. This is going to go into the RHA exhibition or one of the big auction houses and make a lot of money you know.”

“The RHA!!!” the engineer laughed. “Not a hope in hell.”

“You're very wrong there. It's painted by a revolutionary mind filled with angst and on the selection committee is our very own revolutionary, Yann Goulet the sculptor and when Yann a revolutionary himself though some Frenchie fuckers have been known to call him other names...”

“I don’t know who the hell you’re talking about or do I give two fecks but take this monstrosity away out of my sight please.”

“The fucken whore's skank hole wouldn't take it,” Marsh hissed in the Peacock. “It was the fucken doll's house.”

“What did he say about the rest of it?” asked Davis.

“He said he'd do a better job if he strapped a brush onto his cock.”

“What?”

“I'm only joking. He said the rest was the real deal,” Marsh lied.

Marsh volunteered to hold the ladder while Smith was tidying up some high, overgrown branches in the engineer's garden.

“You go on over to the Peacock and I'll tidy up here, and follow you over in a few minutes.”

“Are you sure?” asked Smith.

“Certain. Go on.” Marsh put all the garden's implements carefully away. Then he came out to the front door and had a look up and down Eglington Road. There was no sign of Smith. He crossed over to where a red Volkswagen was parked, removed a chainsaw and re-entered the house.

While Smith was trying to placate the hysterical engineer, and Davis was being questioned about his art in the Bridewell, an artist on dyes and colouring fabrics was walking past the Blue Lion pub. Heading past Sean Hennessy’s where the Harry White generation once supped and swopped stories he was on his way to Summerhill recalling the street rhyme: ‘We are the boys of Summerhill,

We never worked and we never will.’

Frank Davis In The Bridewell Ponders On His Painting Of Tommy Marsh As A New Born Baby